Bird of Paradise – Charlie Parker

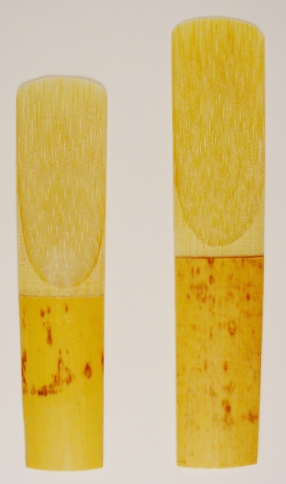

I have written a few times about my lazy relationship with my saxophone, a Boosey & Hawkes silver alto made in 1935 with a Selma C mouthpiece holding a Rico Royal Reed of 3 & 1/2 usually. The reed produces the sound and they come from a plant called Arundo donax, or giant cane.

Any saxophone player worth her salt (like Charlotte Glasson for example) would find a 3 reed way too soft to play. That’s one reason why I say lazy. If you rehearse every day, even for an hour or two, you’ll need to put in a harder reed sooner or later. The numbers refer to the thickness : one is very soft and easy to play, five is tough, needs to be licked on for a minute and you have to blow like a bastard to get any sound out of it, or at least I do. Then again, all mouthpieces are different and eventually you find the reed that suits you. I wrote about my early screechy days with this instrument in My Pop Life #19 then discussed my struggles with tuning and pitch in My Pop Life 80 when I was playing with school band Rough Justice. Later I discussed a disastrous audition for old school chum and Pogues drummer Andrew Ranken in My Pop Life #149 when he was putting together a band called The Operation while I was playing with a group called Birds of Tin. And perhaps my finest saxophone memory was busking Stan Getz, glowingly reminisced through rose-tinted glasses in My Pop Life #68.

Any saxophone player worth her salt (like Charlotte Glasson for example) would find a 3 reed way too soft to play. That’s one reason why I say lazy. If you rehearse every day, even for an hour or two, you’ll need to put in a harder reed sooner or later. The numbers refer to the thickness : one is very soft and easy to play, five is tough, needs to be licked on for a minute and you have to blow like a bastard to get any sound out of it, or at least I do. Then again, all mouthpieces are different and eventually you find the reed that suits you. I wrote about my early screechy days with this instrument in My Pop Life #19 then discussed my struggles with tuning and pitch in My Pop Life 80 when I was playing with school band Rough Justice. Later I discussed a disastrous audition for old school chum and Pogues drummer Andrew Ranken in My Pop Life #149 when he was putting together a band called The Operation while I was playing with a group called Birds of Tin. And perhaps my finest saxophone memory was busking Stan Getz, glowingly reminisced through rose-tinted glasses in My Pop Life #68.

This entry will have to join those stumbles around my chosen instrument if only through omission, because I have never attempted to play any Charlie Parker. Why would I willingly submit to such humiliation? It may, indeed, have been familiarity with those early sides on Dial Records from 1946-7 which prompted me to become an actor rather than a musician. The mountaintop just couldn’t be seen let alone climbed, and I wasn’t entirely sure I wanted to practice for 8 hours a day just to play to a handful of aficionados in a darkened cellar for hardly any money while hooked on heroin.

Then again, as my T-shirt says, it’s never too late to start wasting your life.

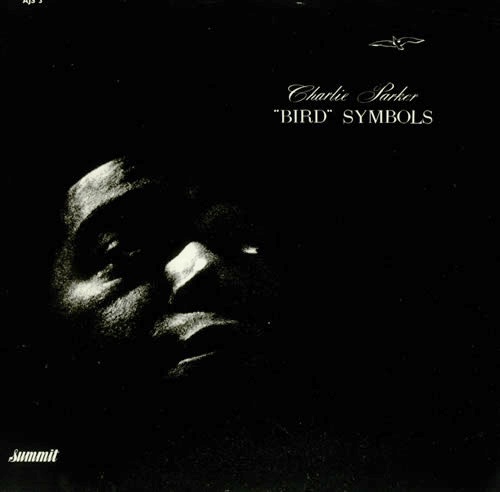

Someone must have told me that Charlie Parker played the same instrument as me. A purely superficial likeness, because I could never even play a single bar of music like Charlie. But I bought an LP with his name on it in my early 20s and played it to death. It was called Bird Symbols and he recorded the sides in 1947. It’s called bebop music, and it broke the mould of jazz, which was in the late 30s & the war years, big-band swing music. Young pups like Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and others reduced the band size down to five or six and stretched the possibilities of phrasing, rhythm, harmonics and even sound itself, producing a schism in the form which then divided fans, critics and musicians alike. Louis Armstrong for example was not a fan of bebop.

Charlie Parker playing his alto early 1940s

Jazz took the high road after this and exploded into a thousand different forms. I knew nothing of this when I bought it, I just listened to a young man playing the alto saxophone and held my breath because what he was doing sounded impossible to play, and for me it still is. There is something so totally confident here, so stretched and bold and strong that I cannot conceive of really being in that space. The opening four tracks of the LP are perhaps his signature sides : Moose The Mooche, Yardbird Suite, Ornithology and A Night In Tunisia pretty much defined early bebop and Charlie Parker, the new demon of the alto sax. They are strange twisted mad tunes, spinning on their axes, interrupted phrases leading to staggering solos, bewitching breathless runs like excited thought patterns as the instruments have conversations with each other, debating the tune, arguing its merits, raising objections, re-iterating the main melody again. They are short explosions of music, all under three minutes long, all totally original, all thrilling. But for me they are all a little theoretical, perhaps too esoteric. The energy is fantastic, the playing beyond impressive. But they don’t make me swoon in the end.

Bird of Paradise is track seven, or track one of side two when you flipped the vinyl over. It is a different beast altogether, slower, contemplative, sweet and gentle and it stole my heart. There is something about the way Parker plays the opening phrase, he kind of falls into it, blowing like he is simply breathing out, making each fluid cadence sound perfectly natural, using the final four bars to sum up a whole universe of feeling which doesn’t resolve but just opens the door for the trumpet (not Miles Davis on this track but Howard McGhee) before pianist Dod Marmarosa turns the beat upside down with a clever phrase that tickles my ears every time. I don’t know how to describe perfection, especially not in jazz, but I have been obsessed with this tune since I first heard it. I have never tried to play it, probably wisely. But there’s still time.

Charlie Parker watches Lester Young playing tenor

Charlie Parker grew up in Kansas City, Missouri. Background notes : the local jazz scene had an R’n’B-influenced swing sound using blues shouters like Jimmy Rushing fronting Bennie Moten‘s Kansas City Orchestra. When Bennie died in 1935, Count Basie formed his own band with some of the players, including Rushing, and innovative stylists Jo Jones on the drums (who started using the hi-hat to keep time rather than the bass drum) and tenor saxophone player Lester Young. Young had a sweet sound when he was backing Teddy Wilson & Billie Holiday (My Pop Life #162) but when he played with Count Basie in Kansas City his long flowing melodic lines, ear-catching pauses and his harmonic & rhythmic daring caught the attention of the teenaged Parker, and every other saxophone player in America. Parker played the Basie sides on his parent’s Victrola over and over again until he had learned every single Lester Young solo by heart. That’s dedication and that’s what it takes to be a great player! Various stories of his early life include getting lost in a solo and losing track of the key changes playing live in a jam session. The drummer – Jo Jones – threw a cymbal at his feet to make him leave the stage but it only spurred him on – an incident grossly misrepresented in the film Whiplash by the way.

Charlie Parker was quoted as saying that he practised in those days up to 15 hours a day.

Not lazy, young Charles.

He was unfortunate though – following a car accident when he was hospitalized and given morphine he discovered that he rather liked the feeling and sought it out in the form of heroin for the rest of his life.

Early picture of Count Basie in New York City

Charlie Parker moved to New York City in 1939 and hooked up with Dizzy, a very young Miles Davis and heroin, and started to practice with bass player Gene Ramey, trying out harmonic innovations in his time off from the gigs he had with the Jay McShann Orchestra. Other instrumentalists were doing similar things – Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Charlie Christian and Max Roach and others were all seeing what they could invent, imagining a different sound, then trying to find it. Eventually a group of them moved to Los Angeles where these tracks were recorded in 1946.

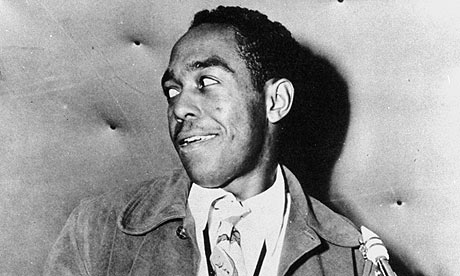

Charlie Parker

There is a good film about Charlie Parker called Bird, starring Forrest Whitaker and directed by jazz aficionado Clint Eastwood. The talent of the man was immense but so was his appetite for being high. That cat was high. Personally speaking, if I even have a joint I find playing music rather more difficult. Especially the piano. What is that note? A? It all becomes rather vague. And drink – well one is fine, perhaps another at the interval, but any more than that and I’m playing like a dick. I’ve always maintained that there are two types of people in the world : People who maintain that there are two types of people in the world, and everyone else. Not but seriously – those who seek oblivion, and those who fear oblivion. I am of the latter persuasion, once I go over my limit, once I start to Lose Control, I stop. I don’t want to wake up in the gutter with one shoe. I don’t want to see what happens if we all go down to the pier and jump into the sea. No. I’m a control freak in that sense. Maybe I’m missing the point but I cannot stand in the shoes of Charlie Parker and imagine what it was like to play those solos while high as a kite. Envious ? Sure, a little. But I wouldn’t trade places with him I don’t think, even though I would say he is probably the greatest saxophone player I have ever heard. I have other favourites – Lester Young for sure, Stan Getz every day, but Parker, when he IS high and he plays a ballad like Just Friends for example from his ‘sax plus strings‘ era on Verve Records, or like this tune Bird of Paradise, well, there simply is no one finer. Listen to him here and melt.

an incredible stoned version from 1947 called All The Things You Are with Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter and Max Roach. It’s the same tune.