Yun Na Thi – Asha Bhosle

..Yuun na thi mujhse berukhi pehle

Tum toh aise na the kabhi pehle..

…you were not so indifferent towards me earlier….

you have completely changed from how you were…

Asha Bhosle sang her first Hindi film song at 10 years old, and had eloped with a man 15 years older than herself aged 16. Three babies later she left her husband with his name and returned to the maternal home in Mumbai, still singing for a living. Her older sister Lata Mangeshkar was also singing Bollywood film songs, but Asha was determined not to just be Lata’s younger sister and looked for ways to follow her own path. This meant often singing the ‘fallen woman’ role in B-grade movies, but as the 1950s drew to a close she and her sister dominated the Hindi film industry having sung more ‘playback songs’ than anyone else. Her speciality was often seen as western-style and more sensual songs. Her success and popularity grew from there. Ashaji is now the official most-recorded singer in world history, having sung over 13,000 songs. Most of these were for Bollywood, but she has also sung ghazals (such as this song Yun Na Thi), Indian classical pieces, pop, folk songs and qawwalis among others. She was the subject of Cornershop‘s single Brimful of Asha (on the 45) in 1997. She continues to sing and tour today, at the age of 82. Some of her greatest work has been the most recent, a duet LP with young Pakistani singer Adnan Sami in 1997, an LP of Indian classical music with sarod player Ustad Ali Akbar Kahn getting a Grammy nomination. But she will always be loved for her Bollywood songs, the mainstay of her career and the Indian music industry.

Dil Cheez Kya Hai from Umrao Jaan

It is impossible to overstate the importance of film songs in the overall picture of Indian music, rather like pop music in the UK, millions listen to it, go to the films and buy it. Among her ‘greatest hits’ which are too many to include on one LP would be Dil Cheez Kya Hai from Umrao Jaan (1981), Dum Maro Dum from Hare Krishna (1971), title track Chura Liye Hai Tumne (2003) and Aaiye Meharbaan from Howrah Bridge (1958).

She sings in Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Marathi, English – in fact 20 languages in all. Perhaps the most remarkable facet of her long life and singing career has been her relationship with her sister Lata Mangeshkar, who is the 2nd-most recorded singer in history, and is herself still singing aged 85.

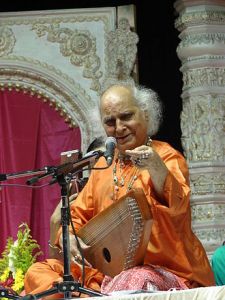

I didn’t hear any Indian music when I was growing up – apart from Sgt. Pepper’s Within You Without You, and Love You To (Revolver) or Peter Sellers taking the piss. Ravi Shankar came to educate us all in the ways of Indian classical music, having made friends with George Harrison, and received a standing ovation for tuning up his sitar at his first English concert. He smiled and thanked the audience for appreciating his craft and hoped they would enjoy the actual music. Then we saw what he could do at the Concert For Bangla Desh. But Ravi was the classical end of things – a sitar player. Asha Bhosle was the filmi end of things – a singer.

Part of the problem for western ears are the instruments used : sitar, tabla, sarod, dilrubi, saranga, bansuri, tambura, shehnai, swarmandel, harmonium. We used some of these instruments when we played The Sgt Pepper show, eg the swarmandel as played by George in Strawberry Fields Forever.

Sarod Swarmandel player Sarangi

The other part of the problem is the pitch – shruti – in hindi which translates as the smallest possible difference in pitch the human ear can distinguish between two tones. Thus our 12-tone scale, in Indian music becomes 23 tones – quarter tones to us westerners, often heard as “blue notes” ie notes sung in a blues between two other notes, either sliding up or down. Pianists are unable to play blue notes – they can’t bend the note like a singer or guitarist or saxophone player, but they overcome this by playing the two notes alongside each other together, creating a dissonance which is rather pleasing. Indian music to my cloth ears relies heavily on these subtleties of pitch which seem to appeal directly to the heart and the emotions. When Lloyd-Webber employed AR Rahman he called it “cheating” but really, what does he know ?

*

Within weeks of starting my law degree at LSE I had a steady girlfriend. Mumtaz, who I called Taj, was born in Aden (Yemen) to Pakistani parents, the family had then moved to Karachi in the 1960s. Mumtaz was schooled in Murree, in the foothills of the Himalayas, near Kashmir. She had come to London to study law, and having graduated the summer before was now studying for part 2 of the Law Exam. Over the next nine years we would be, off and on, a couple. Most of that time was spent in an attic flat in Finsbury Park as we both established footholds in our chosen careers. Mumtaz’ parents never accepted me as a potential son-in-law because I am not a muslim, and although Taj’s older sister Naz had married an Englishman, it hadn’t lessened that pressure, and maybe made it worse.

Taj introduced me to north Indian cuisine, and I can still cook basmati rice, perfect every time, rogan jhosh and and keema peas. Taj taught me how to cook pitta bread – lightly brush water over each side then lightly grill it until it starts to puff up then whip it out, cut in half, careful not to burn your fingers. We ate regularly at the Diwan-e-Khas in Whitfield St, and the Diwan-e-Am in Drummond St. I learned all the spices, some Urdu, some basic tenets of islam. And we saw a few Indian movies, with singing. Not so many, but enough to introduce me to the whole world of Bollywood: Awaara, Pyaasa, as well as the more serious Indian cinema of Satyajit Ray & Mrinal Sen and Mehboob Khan’s epic 1957 film Mother India. I found some Bollywood cassettes somewhere, bought them and played them, their incredible arrangements, timings and melodies started to work their way into my ears. Indeed one of these tunes I CANNOT REMEMBER WHAT IT’S CALLED OR WHO SANG IT, (but it wasn’t Asha or Lata or Mohamed Rafi) became the basis for a song I wrote for Birds Of Tin, the band I was playing in at the time with Joe Korner – a song called Dangerous Garden. In fact I think the cassette was by Shamshad Begum. More about Birds Of Tin on another day. Mumtaz also introduced me to the Beach Boys LP Holland, the band Earth Wind & Fire (My Pop Life #21), Fulfillingness’ First Finale and The Isley Brothers.

It was hard leaving Mumtaz. Very hard. I had three attempts, and twice went back, tail between legs. But the third time it had to be done. Taj didn’t agree, but we had no future together. It just wasn’t right. I ended up in Bob Carlton’s flat in Bow in a tower block, with all my books and none of my records. I never saw my records again. Taj’s revenge. Well, records : they’re just things, right ? as this blog will testify…..

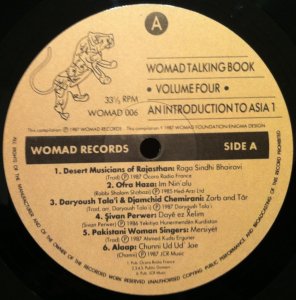

In 1985 I was a disciple of WOMAD. World Of Music Arts & Dance. I bought their first LP Music and Rhythm (see My Pop Life #4) in 1982 and had spent the next three years listening to anything that wasn’t some skinny white kid playing guitar – south african township jive, calypso, greek songs, jazz, classical, gypsy music, arabic, congolese soukous, samba, algerian rai, flamenco, salsa, showtunes, mexican pop music, and hindi film music, what a beautiful world of music there was out there and I wanted to eat it all up, to explore, to mine those golden seams of rhythm and melody, to hear strange languages, strange beats, unusual instruments, see then how things joined up, how distant relations were joined, the cuba-congo axis, the irish/scottish/quadrille/african birth of jazz in New Orleans, the music of Brahms and Jobim, Eric Satie and Oum Kalthoum, the Bhundu Boys and Sergio Leone.

So when WOMAD brought out a Talking Book LP called Asia 1 I immediately bought it full price and consumed it with joy. Asha Bhosle sang Yun Na Thi as the last track on side B. Well, you can’t follow that really. Indeed, how foolish it is to create an LP of “Music From Asia” – which included the desert musicians of Rajahstan, Kurdish music from Siwan Perwer (brilliant), Yemeni Ofra Haza, tabla solos, Iranian goblet drummers and Temple musicians of Sri Lanka ?? Absurd to group them all together – but – it was a sampler made especially for people like me who were trawling the world for their music, who’d got fed up with the radio, whichever station it was, who wanted to explore with their ears. It was, I have to say, a completely brilliant album, but the outstanding songs on it were from Şivan Perwer and Asha Bhosle.

Ashaji had made Abshar-e-Ghazal – the source album for this track – as a break from Hindi film music. She was a hugely respected and wealthy star in India, had restaurants in the Gulf and could do what she wanted. She wanted to do some more classical and traditional music. All the music on the LP was written by Hariharan and the lyrics are ghazals – an ancient pre-islamic form of poetry. As near as I can get to an understanding of this form is the Sonnet – all of the rhymes must be a certain way. A ghazal is a love poem, always about unrequited love, and often takes the Sufi form – a poem about love of God, the ultimate unrequited love. A famous Persian ghazal poet Rumi, who died in 1273, is known a little in the west, although scarcely enough – but the ghazal goes back at least 500 years before him.

I’ve asked for translations of the words to this ghazal, when they come I’ll add them to this blog. Perhaps the unrequited love is Mumtaz’ for me.

Yun na thi mujh se berukhi pehle

tum toh aise na the kabhi pehle

jismeain shaamil tunhaari marzi thi

humne chaahi wahi kushi pehle

jab talak woh na tha toh ai raahi

kitni aasaan thi zindagi pehle