This post relates to the previous post My Pop Life #256 Mother

*

A few weeks after I’d posted that letter I received a postcard from Mum. I can’t remember what was on the cover, but I’ve still got it, somewhere, in storage. On the back of it she’d written

Dear Ralph, Listen to Bird On A Wire by Leonard Cohen love Mum

So I did. I didn’t know the song because I’ve always had a prejudice against Cohen, who knows where it started, but it was confirmed when the twerp who directed my screenplay feature film New Year’s Day in 1999 (see My Pop Life #226 Exit Music (For A Film)) announced one day that Leonard Cohen was the greatest musical artist ever. “Oh well”, I thought. “Never mind”.

I sought out the song, found it on Youtube, put on the headphones and listened. Jesus H. Christ.

Like a bird on the wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free

Like a worm on a hook

Like a knight from some old fashioned book

I have saved all my ribbons for thee

If I, if I have been unkind

I hope that you can just let it go by

If I, if I have been untrue

I hope you know it was never to you

Like a baby, stillborn

Like a beast with his horn

I have torn everyone who reached out for me

But I swear by this song

And by all that I have done wrong

I will make it all up to thee

I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch

He said to me, “You must not ask for so much.”

And a pretty woman leaning in her darkened door

She cried to me, “Hey, why not ask for more?”

It was so devastatingly on the nose I couldn’t believe it. It was astoundingly eloquent and painful, honest and real. It chimed with me in this way too – that my Mum had chosen to reply to the most honest and painful letter I’d ever written to her with a song. Her Pop Life. I wrote about Mum a few times in here, but My Pop Life #147 Days is probably the most positive. I printed it out and posted it to her about four months ago. Perhaps My Pop Life #112 The Night is the least positive. I didn’t post that to her. Yin & Yang.

I find it almost as difficult writing about my relationship with my mother as it is having that relationship. But not quite. Because here I am.

I remember good motherly moments. In Selmeston I was filling a hot water bottle from the kettle and poured boiling water over my hand, dropped the hottie and rubbed the hand in a classic schoolboy mistake. I was still at primary school. All the skin came off and boy did that hurt. Raw. I remember getting a lot of love that evening from mum – no details in my memory like calendula cream but the hand was certainly bandaged and cocoa was made.

The entry called Days (see above) concerns positive afternoons at The Sand Pit watching butterflies with Mum, Paul and Andrew, sometimes cousin Wendy was visiting from Portsmouth. An oasis of peace and good memories.

When I decided aged 11 that I no longer wished to attend Sunday School at The Vicarage she accepted it immediately and made no fuss of any kind. Grateful for that !

And more than grateful for the Sunday early evening ritual of Pick Of The Pops on Radio One with Alan Freeman. Without fail. The weekly chart countdown, from 30 to the Number One. We would play along, sing along, cheer for our favourites, sulk through the bad songs. Embedded in my pysche. A love for Pop Music.

And then there’s the not-so-motherly moments. These commenced early in 1965 when Mum had a Nervous Breakdown and was admitted to hospital to recover. Her Mum, our Nan, came up from Portsmouth to the East Sussex village to help Dad look after me, seven, and Paul aged five while Andrew, just under one year old, went in the opposite direction to be cared for by Aunty Valerie, Mum’s sister in Pompey. Mum was in Hellingly Hospital for nine months. Mainly blotted out of my memory – but pieces of it remain in My Pop Life #55 Help!

I started to build the walls around my heart that year. After Mum came home it seemed as if normal had vanished forever. Dad was kicked out by Mum, they got divorced when I was eight years old. About eighteen months later (?) Mum had remarried to John Daignault. (Pronounced like the French, ie Dag-Noh his parents were French-Canadian). They fought regularly but also seemed to love each other.

But once we moved away from the village in 1970 (see My Pop Life #84 All Along The Watchtower) things changed. We were all separated for nine months in different families in different locations. When we eventually got rehoused in Hailsham (without John Daignault – Mum would say “Dag-Know-Nothing” lol) things would get seriously weird. By now Mum had been diagnosed as a manic depressive AND a paranoid schizophrenic and any other words that were in vogue at the time, and had been prescribed in-vogue and experimental drugs to match all eventualities. As discussed in Help! she was one of many women who were used as guinea pigs by the medical profession in the 60s & 70s, as depression and its variants were slowly acknowledged. They were in the top cupboard in the kitchen, behind my chair. She would ask for one or another of these tablets regularly – Melleril, Librium, Stellazine – and others, prescribed to see what they would do, all different colours, upper or downers who knew. There would be violent episodes as we grew bigger and mouthier. Second husband John Daignault appeared (again), then disappeared after a fight with Paul and I and another when Mum was pregnant with Rebecca. Her episodes got more and more random, surreal and dangerous. Often I would be ordered to walk to the phone box 500 yards away and call the doctor. I was fourteen years old, and had to grow up fast: “My mother needs some different medication/treatment/hospitalisation” I cannot remember any of the conversations but I do remember it was the thing I wanted to do the least. I dreaded those walks to the phone box. At some point in the 1970s we had a telephone installed in the house. A trim phone. But the violence lurked, the threats, the sobbing fits, the midnight crawls around the carpet, the fights with the swinging arm often containing the poker though it rarely connected. It’s all blurred now. We all adapted in different ways, inside our own heads and our own lives. Paul and I shared a bedroom being two years apart in age, so there was some solidarity there. Andrew had his own bedroom and some privacy but must have been lonely and isolated. Rebecca was just a child.

By the time I got to the sixth form I was spending more and more time away at the Ryle‘s house in Kingston where I played in a band with Conrad . I had four or five surrogate families over this period of school – the Korners also took me in more than once (My Pop Life #64 Fresh Garbage) so did the Lester family in Chiddingly (My Pop Life #245 Double Barrel) and Sheila Smurthwaite took me in twice, once in Ringmer and once in Lewes (Watchtower). I relished all these weeks away from my mother and from Hailsham, I got to spend time with what appeared to be happy people, actual families who functioned relatively normally and spoke to each other with love and affection and support. I am so grateful to all of these families for literally saving my humanity. By then I had built the castle wall around my heart and become a survivor replicant, but Rosemary Ryle, Shirley Korner, Sheila Smurthwaite, and Mrs Lester all managed to find a way behind that wall, and so did their children – all my age – Conrad Ryle, Simon Korner, Pete Smurthwaite who died two years ago sadly, and Simon Lester. We all remained close friends. They stopped me from becoming bitter. From being a criminal. As did my other friends whose houses I did not crash in, but who nevertheless were there for me : Andy Holmes, Andrew Taylor, Shirine Pezeshghi, Pam Norris, Julie Furth.

Did Paul and Andrew have these support families too? Paul often stayed with Gilda in the village in the early days, but once Hailsham happened he fell in with Vince and some other Hailsham people – Richard and others. Andrew was at primary school through most of the 1970s and I’m ashamed to report that I cannot remember whether he developed these emotional supports, these escape families like I did. In this sense, I abandoned him much like Mum and Dad did. And Rebecca. God knows how she made it through with such a great sense of humour, because she is as funny as fuck and a real tonic whatever is going on. Neither of us are really talking to Mum any more because it is still abuse that we receive on the whole. It has taken its toll.

The abuse started when I found these escapes.

When I got home I’d get it from Mum. “Spending time with those people, going to parties, leaving me here” kind of stuff. Guilt tripping me, just being nasty. She did come to see me in a school play when I was 16, and Dad came too, they sat together, they were probably proud as punch. I don’t want to paint a false picture of misery and mental illness. It isn’t that simple. None of us went into care at any point. None of us ended up in prison, or overdosed on heroin. We adapted. We survived.

Things didn’t get any better as I left home and went to work in Laughton Lodge, a hospital “For The Mentally Subnormal” (oh those 1970s). I was a good nurse. Saved some money and went away to America with Simon Korner for five months in the summer of 1976. An amazing trip (see, for example My Pop Life #235 You’ve Got A Friend), then came back and immediately went up to London for my first year at LSE. I’d successfully escaped. Paul had been kicked out by then and was working in the Tax Office in Eastbourne, living in Pevensey Bay. Andrew was at Hailsham School. Rebecca was at Primary School.

Mumtaz was my girlfriend through college and we would go down to Hailsham to see everyone, sometimes at Christmas. There were always dogs and cats around. I’m not a huge fan of Christmas.

One Easter we went down and Mum was having a serious breakdown, waking us up in the middle of the night crying, cursing us both for “going to parties and having a good time” and then crawling around on the floor gasping for breath and cursing the doctors. It was an extraordinarily horrible weekend and I don’t think Mumtaz went down again after that. Mum was racist anyway. ( I wrote it as my first play in 1986 and called it Drive Away The Darkness, kind of my version of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Got a reading at The National Theatre and that was that.)

But Paul and I made the error once we’d both returned from our Mexico adventure (see My Pop Life #31 Enough Is Enough) and went down for Christmas. Mum had bought a VCR which will probably date it, and bought a video for us to watch – The Belstone Fox. She then decided that we would be watching it at 10pm on Christmas Day. This clashed with King Of Comedy on C4 (will also help date it if I could be bothered to look it up – the 80s anyway {1984}) which all of us wanted to watch. No. We tried to explain that the VCR meant we could watch The Belstone Fox any time we wanted to, kind of the whole point, but No. We were watching it at 10pm Christmas Day. Voices were raised, drinks were knocked back, things may have been thrown. Paul and I ended up down the pub in the High Street nursing our wounds and Mum went across the green to a neighbour. We never went down on Christmas Day again, and started to hold “Christmas” in mid-December then all do our own thing on the 25th December. What a relief.

The dysfunction continued. I left Mumtaz and started to date Rita Wolf. Mum regularly delivered nasty phone calls mixed with calls where she would talk at me in a stream of consciousness rant for an hour – barely room for an MmnHm then she’d hang up and I’d say to the now dead phone “How are you Ralph?” I suppose it depended on what drugs she was taking, or not. Whenever the four of us would get together (once Becky was old enough to travel independently) – I’m remembering parties in Archway Road N6 where we would try to make sense of it together in a tight group and no one else could get a word in, what did they know of Heather our mother? It became an open therapy session where we would get the latest from Becky and talk about a phone conversation or the new third husband Alan. Alan is a decent man – he treated Becky as his daughter, and still does to this day. Bless him. Andrew went to college and Mum & Becky moved to Polegate into Alan’s house and the story continued. Sometimes it felt good around this period – we all hooked up for birthdays and Alan’s son Mark would be there, we’d talk about hip hop which we were all fans of and by now I was with Jenny and she was witnessing all the nonsense first hand.

Was Mum a victim or a Perp? Had her life conspired in such a way as to give her nervous breakdowns? I always felt dutiful towards Mum even though I didn’t like going home. Always felt sorry for her and used to blame my dad as I said in the letter. But slowly I began to separate the mental illness from the person. She could be remarkably unkind. But took me years to do this separation in my mind because it was excruciatingly difficult, while slowly stitching my relationship with my father back together thanks to his patience & kindness and my own understanding that I liked having a relationship with him, and I didn’t need to stay angry. The middle years I suppose. I was in therapy for a while, I’ve been on anti-depressants for a while, I diagnosed myself as Bipolar, Paul did the same, Andrew reckoned he was Borderline Personality Disorder – confirmed by professionals – the words change but the feelings are what they are. Dysfunctional family alert. Unpredictable behaviour. Individual may need drugs, therapy, love, support and to think before speaking.

Without nailing down the dates, Mum divorced Alan just after the time when Jenny and I bought a house in Brighton. She left the Polegate house and found a small cottage in Willingdon, just outside Eastbourne. She lived there with her two dogs – Trish & Jason – and used to walk to the shops and up to the beautiful South Downs once a day and now and again take a bus into town. Becky was in Strood by now with John Coleman 2nd husband and father to Mollie, Ellie and William. Andrew was with Katie in Bournemouth and they had a son – Alexander. I remember these as happy times. I used to drive over from Brighton to Willingdon – a lovely drive along the A27 across the Ouse and Cuckmere valleys – or along the coast through Seaford to Jevington and turn left. The dogs would bark at me, then approach gingerly, then show affection eventually. A bit like Mum. Suspicious and untrustworthy but happy to see me. We would drink tea and smoke cigarettes and listen to music. Sit in the garden. Jenny had had one insult too many though and never accompanied me on these trips. No need. One day Mum had read a newspaper piece on me talking about Withnail & I – my youth in Lewes smoking weed with the hippies and bikerboys & my mates. She was furious (on the phone to Jenny) telling her I’d let the image of Lewes down with my drug-taking stories. I won’t indulge in the grand ironies present here but Jenny simply said she didn’t agree and it was the truth and Heather hung up on her. Jenny called her straight back and told her never to do that again. Mum apologised, they’ve hardly spoken since – Becky’s birthday maybe.

These were my years as number one son. Paul was abroad and Andrew was in Bournemouth. Perhaps they were getting the abuse then – their turn. Probably though it was Rebecca. We were never all in favour at the same time. And I would go mainly for guilt reasons because she was my mum. What did I get back? Some affection, some love maybe, more interest in my cats than in my wife. It is extraordinary that when I try to remember the bad times they hover just out of reach and I feel like I am betraying my own mother even writing this down. I’m not. I’m being true to myself.

There was a narrow staircase going up to the bathroom and two tiny bedrooms – it was like half a cottage really. The rural poor. As her legs and lungs started to get weaker, the stairs became an issue. I know that she would sit down and go up backwards on her bum. The knees couldn’t manage. The walks ‘up the Downs’ had finished. Someone organised a health worker to visit and Mum would be using a commode and sleeping downstairs. Watching TV eating chocolates pottering around. Eventually – and this took forever – she accepted a move to a bungalow – no stairs, accessible bathroom – on an estate in Hailsham. Town Farm where we’d lived in the 1970s. The painted ponies go up and down.

Becky finished her marriage to John and moved down to Hailsham around this time too. Mum became noticeably grumpier too. Perhaps the medications changed. It was never as relaxing or pleasant visiting her in the bungalow. But what am I actually saying? I feel like I can resurrect some kind of timeline without really tapping into the truth here. So frustrating, so opaque and confused.

In general it has been impossible to share my true feelings because – well, they are unacceptable in polite society. For example, I remember I was writing a screenplay for producer Robert Jones in 2002 and we had a meeting in his Soho office chatting away when I said something like “actually I don’t like my mum” and he was so shocked I don’t think he looked at me the same way again. (we did a TV show in 2014 called Babylon which I acted in later on though.) Society and most people rightly place their mothers at the very top of the tree of respect. She bore you in her womb. She birthed you, breast-fed you, taught you to speak and walk and fed and watered you. I get it. And she did all that. But then something happened.

I think Mum is a vulnerable bully. A phrase I created in my 30s. Accurate. Weakness and power. She is a powerful woman, no question about it, she has powers too. But always presented in this wobbly weak-voiced way until the switch. Then vicious, merciless, darkness.

Although I whinge & whine about the treatment I got, Becky my sister had it far worse than any of the brothers. She is the closest to her mum, and moved down to Sussex from Kent to be closer to her and got years of aggro & abuse as thanks which became physical eventually. Becky stopped talking to Mum in 2017 and we protected her by filling in, phoning and visiting. Then one day Bex had an argument with her man and walked out of the house into her car and drove round to Mum’s. She still doesn’t know to this day why she did it but as she drew up in the nearest parking space there was smoke pouring out of an open window and she ran into the back door where Mum was sitting. The kitchen was on fire. She somehow dragged Mum outside into the garden under protest and called her friend Jan and the Fire Brigade who were both on the scene within minutes. A neighbour took the dog and Mum was taken to hospital, and eventually into sheltered accommodation since it was felt she could no longer look after herself. What are the chances of that? We all have powers, unacknowledged, unused. Three months later she was back in the bungalow, until it became clear after another fall that she wasn’t physically strong enough to walk herself around the place, even with a zimmer frame. Now she is permanently in a nursing home in Polegate and has lost her independence at the age of 85.

It isn’t going to all fit into one blog and neither should it. I cannot recall the early 2000s when we were in Brighton & LA, and Mum would write stink letters to me, and sometimes I’d reply. It was always feast or famine, you’re not good enough as a son, you should be ashamed of yourself travelling around the world while I live here. She was always sick to the back teeth of someone or other, a doctor, a neighbour, a husband, a daughter. Eventually in 2009 I wrote the letter to Mum which appears in My Pop Life #255 Mother – and I sent or emailed copies to Paul, Andrew and Becky too. They all supported me. I was grateful. Then I got the postcard reply.

I was gobsmacked to be honest. There is something indestructible about my Mum. There was some renewed respect. But it was also a cowardly response, not to write anything meaningful, apologetic or honest. Just “listen to Bird On The Wire“. No, not good enough. And we wouldn’t become close again because I didn’t really trust her anymore. That had started to disappear when I was eight years old I think, but confirmed in those teenage years in Hailsham when twice a year or more Mum would pack a small bag – I would help her often – and call a taxi to go to Amberstone Hospital for a break – a rest. Another mental breakdown. An episode. Call it whatever you like. And the doctors would approve and the social workers would allow me to look after the family and pay the coalman/milkman and other bills and I wouldn’t even miss a day of school. We all had keys. That was when I stopped trusting my Mum. And she’s not stupid by any means, she has some truly sagacious qualities and sees through people before they’ve had a chance to settle. Finds their weakness or vulnerability. And then pokes them with her insight – it is never kind, always cruel. She did it with Amanda Ooms our friend from Sweden who came with me one day to see her. In a way Mum is an empath but not a particularly kind one. She hurts she feels pain, and she wants everyone else to as well. She always feels sorry for old people struggling, for the homeless or the hungry or the gypsies. So I’m amazed at how she falls back on racism time and time again though because three of my four great love affairs have been with people who suffer from racism because of their skin colour and culture. And I don’t forgive that in particular. The reason I stopped speaking to Mum two years ago was when she said – in a phone call from New York to East Sussex, after Jenny’s sister Dee had died at the age of 59 after an operation and we were struggling with the grief –

“You love Jenny and all those black people more than me don’t you?”

The cruelty and the unkindness felt instinctive and also calculated. The mental illness feels like a disability. They’re entangled like a load of useless wire behind the television, but when the picture goes you have to sit down and untangle it all. I have spent my entire adult life untangling those wires. And I decided after the last attempt to to insult me and push me away that I would stay insulted and stay away. Fuck the wires. We haven’t spoken a word since.

What is also tragic though is that she understands all of this, she has both intellectual and emotional intelligence – more than most in fact. And her choice of song reveals that.

“I have torn everyone who reached out to me”

And thus she remains unforgiven.

She has often talked about wanting to live in a cave, not wash, not see anyone except her dog and the birds and insects. I’m not going to help her with that.

She is like a shadow over all of our lives. And an absence too.

*

I saw Leonard Cohen in Brighton in 2013 when he was 79 years old. He did three encores, and 28 songs in all, putting the kids to shame. Bird On A Wire, perhaps his most revered and famous song was number three on the setlist. It pricked me like a sea urchin, shivered my timbers and brought water to my eyes. Also present : Dance Me To The End Of Time, Famous Blue Raincoat, Hallelujah & Chelsea Hotel #2. He did not sing Joni Mitchell’s A Case Of You, supposedly about their affair in the early 1960s, two Canadians in Greenwich Village singing songs and writing poetry to use as lyrics. He was elegant and wise, generous and inspiring. He died in 2016 three years later.

Bird On The Wire is a stunning piece of songwriting. I have tried in my way to be free. Yes we can all relate to that. I have saved all my ribbons for thee. Well no you haven’t. And is that appropriate? I’m your son, not your lover. Quite oppressive if you dig a little deeper, quite possessive. Quite fucking weird. If I have been unkind, I hope you can just let it go by. Well yes I can. I have. I’ve let it all go by. Thank God. If I have ever been untrue I hope you know it was never to you. Simply not true. Abandoned too many times for that to be even half true. Also slightly oppressively incestuous. I have torn everyone who reached out to me. No doubt. No doubt. It’s the most honest line in the song. It’s an appeal for forgiveness – is it? It certainly isn’t an apology. I will make it all up to thee. Way too late for that. In 2009 I was 52. Childhood gone. Romantic. Delusional. And didn’t.

I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch

He said to me, “You must not ask for so much.”

And a pretty woman leaning in her darkened door

She cried to me, “Hey, why not ask for more?”

Amazing lines. The crucible of life’s contradictions. The balance. Do I feel good about myself? Didn’t I do enough? What’s it all about Ralphie ?

I’m out of gas on this topic. Time to publish and be damned. I still don’t like my mum. Forgive me.

Mum always did have good musical taste. So, from Cohen’s Anthem :

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

*

changed lyrics in this live version from 1979 :

Presenter Peter Snow (right) had an SDP poster up in the room where he was working. I desperately wanted to ask him if it was his, but couldn’t find the words. It was very very difficult to ask journalists about their politics. They pretended they didn’t have any. Or they said ‘I’m nosy’ or ‘I’m an observer.’ Others were more approachable, notably those at The Express, where a considerable number of the writers are members of the Labour Party! I was devastated by this disclosure, although the Express journalists I spoke to found it totally normal : ‘It’s the same at the Mail, the Sun, the Telegraph. You’ve got to earn a living.‘ I suggested the two things might be incompatible. ‘I’ve never written a word against the Labour Party in twelve years on the Express.’ The man seemed proud of this, as if his principles were still intact. Fiona Millar, one of the few women on the paper had an even worse situation, surrounded by pin-ups, being given the Royal stories or the animal stories because of her gender. ‘My generation is terribly disappointed in the profession we’ve joined,‘ she told me. She is in her late twenties, and moved from the local paper to Fleet Street just as it was going down the drain : bingo, tits and circulation wars. She was consoled by the fact that the Express was ‘a writer’s paper’ rather than a subeditor’s paper. Subeditors – the back bench – are a strange group of men (invariably) who sift the paras, reorganise the stories, and in many cases rewrite according to the paper’s politics.

Presenter Peter Snow (right) had an SDP poster up in the room where he was working. I desperately wanted to ask him if it was his, but couldn’t find the words. It was very very difficult to ask journalists about their politics. They pretended they didn’t have any. Or they said ‘I’m nosy’ or ‘I’m an observer.’ Others were more approachable, notably those at The Express, where a considerable number of the writers are members of the Labour Party! I was devastated by this disclosure, although the Express journalists I spoke to found it totally normal : ‘It’s the same at the Mail, the Sun, the Telegraph. You’ve got to earn a living.‘ I suggested the two things might be incompatible. ‘I’ve never written a word against the Labour Party in twelve years on the Express.’ The man seemed proud of this, as if his principles were still intact. Fiona Millar, one of the few women on the paper had an even worse situation, surrounded by pin-ups, being given the Royal stories or the animal stories because of her gender. ‘My generation is terribly disappointed in the profession we’ve joined,‘ she told me. She is in her late twenties, and moved from the local paper to Fleet Street just as it was going down the drain : bingo, tits and circulation wars. She was consoled by the fact that the Express was ‘a writer’s paper’ rather than a subeditor’s paper. Subeditors – the back bench – are a strange group of men (invariably) who sift the paras, reorganise the stories, and in many cases rewrite according to the paper’s politics.

Grand Hotel, Brighton, the morning after an IRA bomb, October 1984

Grand Hotel, Brighton, the morning after an IRA bomb, October 1984

A young Simon Curtis in 1985, one year after Deadlines

A young Simon Curtis in 1985, one year after Deadlines

Camden Lock

Camden Lock

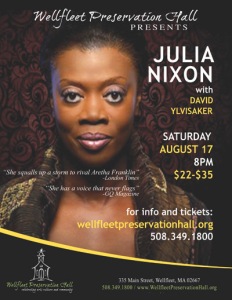

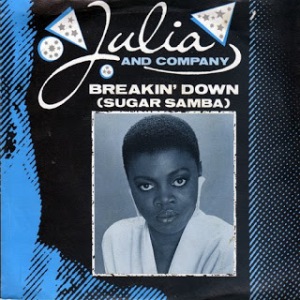

Knowing nothing about this group until recently when I learned that Julia Nixon had replaced Jennifer Holiday in Dreamgirls on Broadway, and that after this cracking single in 1984 and the follow-up I’m So Happy, she finally released her first solo LP in 2007 some 23 years later.

Knowing nothing about this group until recently when I learned that Julia Nixon had replaced Jennifer Holiday in Dreamgirls on Broadway, and that after this cracking single in 1984 and the follow-up I’m So Happy, she finally released her first solo LP in 2007 some 23 years later.